FAIR MANAGEMENT AND SUSTAINABLE

PRACTICES: On

Corporate Social Responsibility in the Market Economy

By Pr Philippe Daudi & Dr Charbel Macdissi,

MCF & Elena

Tonetta

Abstract

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a rewarding intellectual activity as

well as an insight provider in dimensions that matter in man kind activities.

The depth of one’s involvement in the subject is probably proportional

to one’s engagement in the ongoing broad discourse of fair management

and sustainable economies and practices. During the last decade or so, we have

witnessed an increased interest in the subject triggered by many reasons. The

ever increasing “market mania”, its subsequent harsh environment

and unstable labour situation create a strong sense of uncertainty with regard

to how firms are handling their social responsibility. Turbulence on the market

places jeopardises jobs and leads to an increased awareness of the general public

that CRS or lack of it can have tremendous social effects on the everyday lives

of communities. Especially those communities with strong economic dependencies

to locally established firms. Many reports of misdeeds have invaded the front

pages of the newspapers lately. The amplitude of some of these misdeeds are

of such shocking magnitude that the issue of firm’s honesty and responsibility

have become the focus of the general public as well as that of the controlling

and legislating instances. Thus the aim of this article to look at CSR from

a broad perspective, that of business ethics, and fairness and sustainability

of business practices.

Introduction

The governing ideas on CSR have acquired more and more acceptance and their

manifestations are the subject of many studies. Furthermore, CRS seems to have

become an integrated part of many firms everydayness. In many cases, accountable

practices of CRS, are likely to increase the chances of a firm to keep its position

and competitiveness in the view of general public. What the public sees in the

practices of CRS is the overall behavioural pattern of firms in terms of the

businesses choices they make as well as in term of their societal attitude,

or societality. The public, the governments of different countries and firms

are today equally interested in developing and implementing CRS in the market

economy. Despite the fact that interest in this issue varies widely across different

countries due to political traditions and degrees of awareness, it appears important

that a convergence is achieved.

However, this is not always the case. Public institutions of different countries

might interventionist at various degrees. Different groups of consumers around

the world are certainly interested in different issues and looking for different

solutions to their fundamental problem. Businesses might display a social responsibility

for strategic reason. In some cases, although rare, they might also do the same

simply for pure altruistic reasons. In yet other cases, firms might simply exclude

CSR from their reflections and activities.

It is generally agreed that all these groups are becoming more interested in

the development and implementation of CSR in the market economy. Furthermore,

the dissimilarities that can be analysed in different areas have to be accurately

examined and evaluated with particular focus on the consequences of globalisation.

Thus, a visible lack of ethical conduct that translates into actions of misdeed

is a source of a serious damage to the public trust in guilty firms. The scandals

that have exploded in the circles of investment firms, formerly believed to

be solid and reliable institutions, such as Morgan Stanley and Marilyn Lynch

have created a trauma in the public eyes. Similar scandals have appeared in

the world of insurance companies such as Skandia in Sweden as well as in old

and much respected traditional industries such as ABB. Even the state owned

companies appear to have their share of corruption and misdeeds. The case of

the Swedish System Bolaget, a state owned retailing companies providing the

Swedish citizens with wines and other alcohol beverages through an extensive

chain of stores all over the country, reflects the might of the dramaturgy embedded

in the practices of unethical business behaviour. The ongoing investigation

in this company (November-December 2003) have revealed that nearly a hundred

people, mainly at the middle management level, have been bribed by suppliers

in a systematic bargain providing them with substancial incentives for favoring

their respective brands. Further news of misdeed, bribes, unfair treatment of

employee, harassment and suppressions of minimal rights are now a daily routine.

Section 1: Data analysis

In the midst of the torment, PricewaterhouseCooper have conducted an extensive

worldwide survey among 1000 CEOs from 43 countries asking them to share “

their hopes and fears, and their insights” This study is the 6th annual

global Ceo survey and its being done in conjunction with the World Economic

Forum. The study is entitled “Leadership, Responsibility and Growth in

Uncertain times” (2003). The study deals with many problems that are felt

to be significant for the business community such as regaining confidence in

the wake of economic breakdown as well as the latest major terrorists actions.

But the study is also about the prospect of building trust among investors,

customers and employees and reclaiming “responsibility for being good

corporate citizens and good shepherds of the global environment.” About

half of the asked CEOs admit that corporations in their country had suffered

great loss of public trust. They also are positive about the actions taken by

legislators in order to impose standards of accountability to corporations.

As it is stated in the survey, there is a little doubt about the fact that the

latest corporate scandals have been very negative to the international business

community at large. Firms around the world are seriously considering different

options for gaining or regaining the public trust. The case of Skandia in Sweden

is certainly one of the most difficult to repair since the malefaction dealt

with the pension funds of the ordinary men and women. People have seen their

assets diminishing by more than a half while the bonuses of the responsible

CEOs has increased astronomically. One CEO got out of the catastrophic situation

of the company with a golden shake hand worth 25 millions euros. This and many

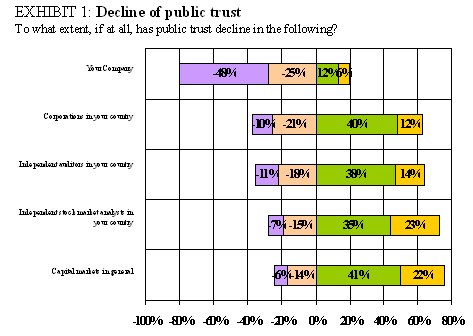

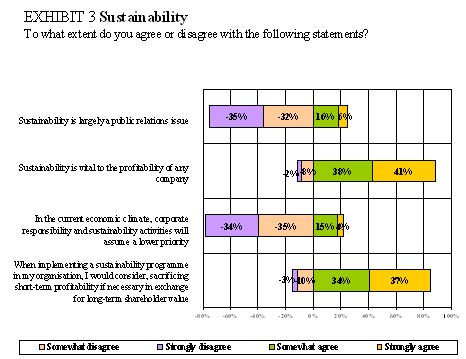

likely events exploding in the media convey but disdain and despair. Exhibit

one (page 16 in the PricewaterhouseCoopers’ CEO report, 2003) depicts

the question as to what extent has the public trust in firms ethical abilities

declined. The decline seems to impact on three key elements: the spirit of transparency,

the culture of accountability and the integrity of people.

One striking finding, as it appears in this exhibit, is that more than 70%

of the asked CEOs report that public trust has essentially declined in other

corporations, in auditor’s actions and in market analysts. However, they

think that their particular firm still have the trust of the public. This is

of course a somehow distorted view of the reality. It is the sort of selective

perception that that bring even more mistrust

Interestingly enough it is also reported in this study that “transparency

and accountability can mean different things to different people”. 53%

of Asia-Pacific CEOs agree that transparency and accountability are “country

specific and culturally sensitive”. They also agree, that “the motivation

of the transparency is more dependent on a company’s visible involvement

than on its visibility in the global marketplace”. The same goes for “company’s

motivation for meeting its CSR”.

Another survey, a small part of which is presented here, done by Ph. Daudi

and Ch. Macdissi in 2003 among firms in Guadeloupe shows that managers in this

region tend to associate CSR with a high awareness of the importance of environment.

The finding shows, for example, a rather positive attitude toward ecology, which

is seen as the expression of national ethic, as a way of life and as the manifestation

of the individual as well as the corporate social responsibility. When asked

to respond to a set of objectives primarily related to their perception of an

ethical behaviour as it might be displayed in their ecological actions, the

ranking of the manager’s responses show a clear positive attitude to CSR.

1- Personal responsibility 91,4 %

2- Common interest 91,3 %

3- National ethic 79,3 %

4- Need for survival 75,8 %

5- Tendencies 39,7 %

6- Restrictions 34,5 %

7- Business Opportunities 25,8 %

The managers have also been asked about their willingness and ability to see

good environmental actions as embedded dimensions in their strategic efforts,

thus viewing these positive environmental positions as competitive strategic

advantages. The majority of the asked managers appear to see positive effects

on their firms. The highest ranking is given to the image of the firm whilst

the lowest to the prospect of increasing the profit.

1- Creating a positive image 98,3 %

2- managing the competitive advantages 75,9 %

3- Attracting customer 74,1%

4- Generating added expenditures 63,8 %

5- Obtaining subsidies 58,6 %

6- Avoiding political sanctions 53,4 %

7- Increasing profits 50,0 %

This been said, a crucial question was asked as to what would constitute the

most important obstacles preventing an CSR and environmental conscious manager

from implementing his/her actions. The ranking hereunder emerging from the answers

indicates a certain ambiguity if one keeps in mind the overwhelming general

positive attitude, which emerges from the ranking above.

1- Financial restrictions 84,5 %

2- The firm concentrates solely on business 81,0 %

3- Lack of ecological awareness 79,3 %

4- Lack of ecological policy in the firm 77,5 %

5- lack of demand from the customer 72,4 %

6- The complexity of the issue 70,7 %

7- Lack of time 62,1 %

8- Personal attitude 56,9 %

The majority quotes the financial restrictions as the primary obstacle to their

projects of implementation, whilst still more than half refers to their own

personal attitude. The lack of ecological policy in the firm and the complexity

of the issue illustrates ambiguous attitude of the managers in relation to what

they stated earlier and given the fact that they are the people responsible

for the introduction of policy in their firms. Even if the managers in this

specific region in Guadeloupe, might have some difficulties in implementing

their ideas, we wanted nevertheless to get at their intentions, perfectly aware

of the risk of their answers being more parade words than personal convictions.

1-Questions concerning environment ought

to be integrated in the managerial decisions 86,1 %

2- Recherche & Development is importante for

limiting the bad impacts on ecology 84,5 %

3- Questions concerning environment ought to be a

major peroccupationfor managers dirigeants

d’entreprise 84,5 %

4- Environmental concern can be perceived as

competitive advantage 79,4 %

5- There is a crisis of the environment 79,3 %

6- Firms ought to disseminate information

about ecology and environment 58,7 %

7- The ecological situation is significant but

not critical 53,5 %

8-The politcs of ecology and environment is merely

an effect of fashion 20,7 %

The intentions and visions of the majority of the asked managers in the Guadeloupe

survey are compatible with those of the managers of the PricewaterhouseCooper

survey indicating the overwhelming global character of the issue of CSR and

related matters, and the will of many to cope with the problems deriving from

it.

Needless to say that the increasing magnitude of ethical issues and related

events constitute disadvantages rather than advantages for firms, thus exposing

their practices to the scrutiny of the public eye. Johnson & Johnson is

a good illustration for a firm’s capability to display and act in a visible

ethical way. This was during the crisis concerning their product Tylenol in

1982 and 1986. The product was made by a subsidiary of the pharmaceutical company,

whereby mysterious persons altered the product by placing deadly cyanide in

it causing the death of seven people. Johnson & Johnson recalled the product

suffering losses for 100 million USD. This was in 1982. Four years later, the

act of sabotage was repeated. This time, Johnson & Johnson has no other

choices but to stop the production of capsule form altogether was and to replace

it with the more secure form called caplet. The situation, even if tragic in

some respects and very costly in others, became however an opportunity for the

firm to show its good will and ethical predispositions towards the stakeholders

at large.

Examples of opposite behaviour to that of Johnson and Johnson are many, unfortunately.

The largely mediatised Enron fraud is probably the most fastidious financial

scandal of the past years. 12.000 employees were involved and thousands ordinary

Americans lost billions of dollars because of frauds made by managers. Other

spectacular examples of misdeeds are those of WorldCom, Tyco, Qwest, Imclone,

Critical Path Inc etc. As James Surowiecki editor of the book “Best Business

Crimes Writings of the Year”, Anchor Books, 2002, asks:

How did this happen? […] CEOs, fed on a diet of hefty stock-option packages

and hyped-up publicity, who came to drink their own kool-Aid, imagining that

they understood what no one else did, and that there were no obstacles to their

visionary schemes. Instead, they made outrageous promises and then found themselves

playing fast and loose with the rules in a desperate attempt to make those promises

come true. Others, though, were more cynical about the process, using the hype

machine to great effect and milking the system for all it was worth.”

(Surowiecki, 2002:4)

Scandals of such magnitude are spreading fear, suspicion and mistrust in Corporates,

in CEOs, in the financial systems as well as in the entire economy (Greider

in Business Ethics 02/03).

Section 2: Theoretical Analysis

2-1/ The Different facets of CSR

The concept of CSR has since more than a decade known a remarkable evolution

in different ways, such as in the understanding of its relevance in the market

economy, in its definition, in the related concepts as well as in the ways it

is implemented. However, the words have had different meanings to different

parties. The ambition here is to find the “nexus between what is in firm’s

self-interest and what is in the general public’s interest”. Merging

economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic issues in the defining of CSR, Carroll

(ibid) highlights its vast context. Combined with the respect of the law, of

the ethical values and of the company’s principles of social contribution,

a primacy is given to economic performances. The broad context of the concept

can be better grasped by looking at some important theories depicting firm’s

behaviour.

2-2/ Corporate citizenship

In literature as well as in common places, the concept of “corporate citizenship”

is both widely used either as a parade or it is misunderstood altogether. The

general view of corporate citizenship merging the individual behaviour with

that of an organisation, reifies firms actions that are then judged and condemned.

Corporate Citizenship is thus associated to the firms’ achievement that

take social and environmental good measures simultaneously with strategic and

financial actions as well as with the efforts of building a viable social image.

To evaluate if a business is socially responsible, it is therefore necessary

to compare what it does with what it can do against a set of criteria for external

and internal possibilities, threats and pressures (Zadek 2001). The study of

CSR should incorporate corporate citizenship and be central to management, since

it is increasingly becoming at the heart of managerial action, leadership, and

strategic choices. It is also central for building corporate image and gaining

public trust.

2-3/ Stockholder and stakeholder

Stockholder: Based on Adam Smith’s classical economic model, this theory

considers that each business must operate achieving its own interests, thus

maximisation profits, since through the “invisible hand” the numerous

interests of the society are simultaneously promoted in an economic, rational

and spontaneous “natural order” (Poma, 1996).

The stockholder theory was advocated by Friedman in 1962 in ‘Capitalism

and Freedom’. The author’s leading thought is “laissez faire”.

It aims at the creation of an economic system based on the individuals with

a limited involvement by the state. Friedman argues that “the social responsibility

of business is to increase its profits […] and the economic values, not

the social values, […] while acting legally, ethically and honestly (Friedman,

1962: 190). Clearly, even though other goals besides profits are identified,

they cannot have priority in the firm’ decision making process. Stockholders’

interest in firm’s performance and the increase of the value of the company

are the essential aspects that must be taken into account. The privileged position

of the stockholders is directly related to them being owners of the property

right, provider of the capital and the risk taker. In conclusion, CSR is implemented

only when it boosts efficiency.

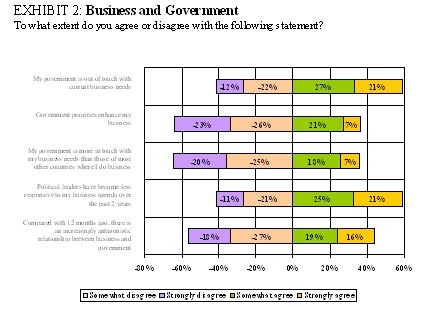

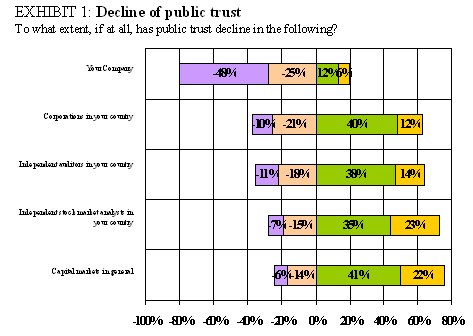

The exhibit above (page 12 in the PricewaterhouseCoopers’ CEO report,

2003) shows an “apparent disconnect between government and business”.

The asked CEOs do not think that the relationship is getting any better but

they seem to expect this situation to remain in a status quo, i.e. not getting

worst. Almost half of the asked CEOs agree that the governmental actions seem

to be quite far from their own business preoccupations. Furthermore, they think

that the political leaders are less and less responsive the CEOs “business

agenda”. The exhibit shows that there is an “increasing antagonistic

relationship between business and government. (ibid)

Freedman’s theory would seem to be somehow short sighted with respect

to today’s debate. Yet, the reality of business practices as it is widely

illustrated by the latest scandals, depicts a picture rather closed to that

of Freedman’s prescriptions. Not that he encourages people to take bribes

and to misuse company’s assets, but he encourages them indeed, although

indirectly, to espouse a selfish and a profit driven behaviour. It is perhaps

naïve to think that the opposite is possible. The human nature might sometimes

be driven by greed and self-interest, but we must nevertheless pursue the ideal

of fairness and ethically viable practices. A narrow and limited view of the

supremacy of economic performances of the firm as sole mark of legitimacy of

its existence is often archaic and incomplete.

Stakeholder: Stakeholders can be satisfactorily defined as “everyone

who directly or indirectly receives the benefits or sustains the costs that

results from a firm’s actions” (Hax in De Wit and Meyer 199: 32).

The stakeholder theory considers that besides stockholders a company must take

other internal and external actors into account, since they can have great impact

on the position of the firm in the market economy. Moreover, as stated by Hardjono

and Van Marrewijk (2001: 225), although “ Adam Smith’s concept of

self-interest is still the driving force in post-modern society, sustainable

progress will only occur when this self-interest is enriched with sufficient

ethical, social and environmental elements”. In order to be competitive

firms must achieve the sustainability of their business practices.

The Exxon Valdez (today renamed as Sea River Mediterranean) oil spill occurred

on the 24th of March 1989. The accident was the consequence of incorrect rigging,

which caused the crash of the ship against an iceberg. Eleven million gallons

of oil were spilled. At that time, the catastrophe had great proportions. The

company spent four years and about 2.1 billion USD on the cleanup efforts, employing

10,000 workers and hundreds of aircrafts, helicopters and boats (Exxon Valdez

Oil Spill Trustee Council). Needless to say that this seemingly commitment was

driven by two main necessities: the necessity to response to a strong governmental

pressures and the necessity to restore some of the firm’s image. In this

case the “ firm must make trade-offs between its goals and the ones of

stakeholders” (Key 1999, p. 320) hoping to accommodate the broad context

of CSR and ethics.

2-4/ Moral hazard and CSR

Arrow in 1963 has raised the question of the moral hazard or risk by analysing

it under its two aspects ex-ante and ex-post. Taking the example of insurances

sector, he showed why all the risks are not ensured. The concept of moral hazard

thus found its origins in an applied case. Its meaning, simply put is that when

an agent is assured he, perhaps, adopts behaviour different from that which

he follows when he is not ensured, which can lead to an increase in the risk.

He/she acts on a situation concretised by a post contractual opportunism where

the policyholder adopts a behaviour knowing that he/she is covered by insurance.

For example, a person might be taking more risks or less precautions (ex-ante)

or she might be acting in a purposeful way, causing an accident with the view

of claiming the insurance funds (ex-post).

The moral hazard is thus revealed by a post contractual opportunism where each

contracting part (or one of them) seeks to draw a unilateral benefit knowing

that the other part does not have the means of completely checking all the clauses

of the contract. Even when such an action is made possible, it would lead to

such discouraging high cost of control and monitoring. Moreover, the opportunist

behaviour would pass better if the other part does not realise its existence

at once, but rather become aware of it only after that the action is carried

out. It is clearly a case of asymmetry of information.

There are a great number of examples of moral hazard. Indeed, each time that

there is a contract, a co-operation, a strategic alliance, etc., which associates

at least two persons or entities, there is a risk of moral hazard.

In their book on industrial economy, Médan and Warin(2000, p.292-304),

refer to a number of interesting examples. According to them, "certain

stockbrokers do not hesitate to encourage their customers to multiply the operations,

even if that is not always in the interest of the customer, but because they

perceive a commission with each operation. More often than not, the customer

is quite unable to accurately check if the transaction serves his/her interests

or those of the agent. However the moral hazard could also be at the source

of an efficient behaviour. Knowing that one is ensured, a person will take more

risks. The actions thus undertaken will obviously have consequences that might

seem efficient. For example, a countryside doctor who does five medical calls

per day, might increase her daily calls to seven because her new car, equipped

with airbag and ABS, gives her the impression to be in security and even encourages

her to drive a little faster than usual. Indeed, even if her behaviour as a

driver is more risky, the fine characteristics of the new car decrease the prospect

of risk, thus that of having an accident ".

Two another examples deserve to be quoted. The first one is presented by Paul

Krugman and concerns the Asian crisis: It is suggested that the Asian crisis

of 1997 seems to find its origins in a concept close to that of the moral hazard.

The investments made by firms in these countries were guaranteed by the different

governments concerned. The mere fact of being guaranteed made these investments

risky. Furthermore, the decreasing surplus gained from the investment was diminishing

the hope for profits. However, as long as the guarantee existed, the play continued

until the concerned governments had could not anymore cover the bank losses,

contributing therefore to the well nkown successive bankruptcies.

The second example is that of crude oil cartel OPEC. At the time of its constitution,

all the states members agreed to respect the terms of the agreement. However,

knowing the positions of the other members as it is inscribed in the agreement,

one of the countries can choose to take a different course of action. For example,

Iraq, acting on an individual basis, decided individually to increase its output

and subsequently its profits. It is indeed a case of moral hazard.

Moral Risk and Theory of the Agency

In his book of industrial economy (1992, p.32-33), Michel Glais analyses the

contractual relations as being “Marked normally by the seal of co-operation,

the contractual relations are not safe from conflict situations imposing procedures

of monitoring and control on the organization by decision makers, i.e. the principal

in agency theory. The procedures are also imposed by the agents who have a limited

authority to carry certain duties.”

Within the frame of this theory, it is assumed that the possibility of divergent

interests of both the principal and the agent increases the probability of moral

hazard on both sides. The same situation might occur between different parties

representing the stakeholders of the firm. Working on the agency theory, Jensen

and Meckling (1976) and Fama and Jensen (1983) showed the existence of these

divergences of interests where different parties would attempt to behave somehow

rationally more often than not lead to an irrational collective behaviour.

Concerning the shareholders and the managers and according to Médan

and Warin (2000) "These divergences of interests but also the asymmetry

of information involve a double phenomenon of moral hazard and an adverse selection.

The moral risk is interpreted as the impossibility for the shareholder (the

principal) of evaluating the work provided by the manager (the agent). The adverse

selection emerges from the impossibility for the shareholder to define with

any precision the conditions of contracts which link her with the agent ".

Incentives

According to the theory of the incentives, within an organization, the incentives

could lead to the reduction or the elimination of the moral hazard. The inciting

mechanisms permit the firms to circumvent the difficulties of the moral hazard.

Among these mechanisms, one can mention the wage incentives, the premiums, the

profit-sharing, the contracts of objectives, etc. A form of incentive was born

initially in the USA and then in Europe: stock options. As we have seen earlier,

the consequences of this system, in some cases, have had quite negative effects

on the morality of leaders. The problematic related to incentive has to do with

several aspects such as the raison d’être of stock options, the

“roof” for incentives if these are related to stock market performances,

the number of people concerned with incentives in the firm, and the role of

the leadership versus that of the board

In the case of the Swedish Scandia, for example, the authors (2003) of the

scrutinising report examining the “Scandia Scandal” are very critical

to Scandia’s incentive system where no roof for how large a bonus could

be is a central issue. Other issues are those of incentives related to the so

called “embedded value”, “sharetracker” and “

wealthbuilder”. In all cases, clear and well defined criteria are missing.

Decisions to ”compensate” managers for their deeds became a rather

fanny play-like piece of bad theatre where good old boys are rewarding each

other the best they could. When the scandal became a fact for every one to behold,

the guilty pleaded that they are merely misunderstood by all and that, somewhere,

it must have been somebody else’s fault that things went wrong. In my

childhood, when did something wrong, we had to pay tree times: one time for

the bad thing that we did; one time for being caught and one time for not taking

responsibility. The grownup children who manage Scandia obviously did not have

the same principle.

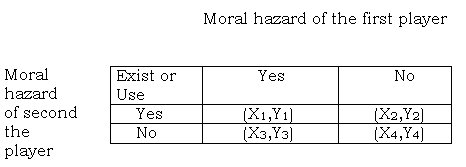

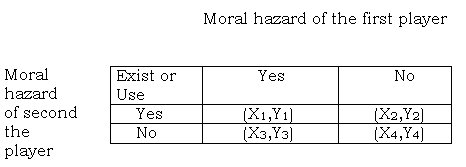

Moral Risk and game theory

With two or more players, the game theory, could be of a great help to formalize

the moral hazard. Indeed in the case of two players, an employer and an employee,

two signatories of a contract, a shareholder and a manager, etc., the following

table represents the situation of existence and absence of moral hazard, and,

in case of its existence, the probability of a player to use it.

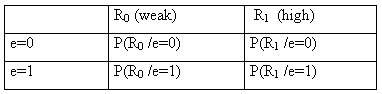

X and Y respectively represent the utility, which each player will draw from

his situation of contractor with or without moral hazard. The ideal situation

would be the absence of moral hazard or the fact that the moral hazard is not

used by the two players. This theoretical situation often leaves its place to

the three other possibilities described in the table.

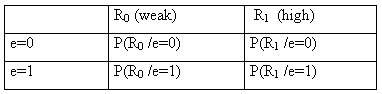

Médan and Warin (2000) present a very interesting approach founded on

remuneration and on the produced effort. They summarize as follows: "If

the utility of the employee depends on his remuneration w and the level of effort

authorized e, by simplification, one considers that there is an acceptable level

of minimum utility. The constraint of the participation of the employee is thus:

U(w, e) > = Umin

The employee can produce various levels of efforts: a weak level (e=0) or a

high level (e=1). However, in the majority of the cases, this level of efforts

is not observable. This impossibility of observing the effort level is at the

origin of the incentives existence”.

Probabilities of emergence of results as a function of the level of effort

P(R1 /e=0) < P(R0 /e=0) and P(R0 /e=1) < P(R1 /e=1)

The probability of having an important result thus depends on the effort provided.

The latter could lead to weak results, i.e., if the result does not depend solely

on the work carried out by the employee but on a great number of other variables.

Thus, there are limits to the application of incentive as a neutral tool of

management.

2-5/ Social contracts

Based on the discourses of important philosophers like Hobbes and Rousseau,

this theory is based on the concept of society as “a series of social

contracts between members of the society and the society itself” (Gray

et al. 1996 in Moir 2001). This notion of contract, virtual or real, reflects

the expectations and requirements of the society at large and of the subsequent

necessity for firms to comply with them. Naturally, it is essential to consider

the temporal and contextual changes of the idea of the contracts and their contents

in order to meet their criteria successfully. Society and all the actors that

operate in it are indeed stakeholders and as such, their influences on the activities

of firms are related to the terms of contracts binding the different parties

to each other and regulating their contributions. Thus, the social contacts

theory, in it support of the stakeholder theory, may bee seen as the broad field

within which CSR can be explained and understood. Donaldson and Dunfee (2002),

argue that about 50 years ago companies were simply expected to charge fair

prices for their products and services, while nowadays they are asked to be

involved in a large variety of social issues such as racial and environmental

problems.

2-6/ Ethical, altruistic and strategic social responsibility

Geoffrey Lantos (2001) has correctly underlined that companies can be responsible

in different ways. Responsible behaviour might be the consequence of external

impositions such as governmental obligations or it might be the result of a

voluntary decision. In other words, the reasons can be the prospect of gaining

some economical advantages or satisfying the stakeholders’ expectations.

Accordingly, it is interesting to discern ethical, altruistic and strategic

CSR.

Ethical CSR refers to all obligations, which have an ethical nature and that

a firm should accomplish by being morally responsible for the effects that its

actions can have on individuals or groups of stakeholders in the society. Since

responsible behaviour is usually expensive and in this view it is the result

of a free choice of the company, ethical CSR reveals that the firm might choose

to put moral values over self-interests and stakeholders’ protection over

profits. “Sometimes actions need to be taken because they are right, not

because they are profitable” (Chewing et al. 1990, Goodpaster 1996, Miller

and Ahrens 1993 in Lantos 2001).

In other cases, however, an organisation might act responsibly also in relation

to harms and situations it has not caused, for example for solving public welfare

deficiencies. Since it embraces a broader set of tasks than ethical CSR, this

behaviour is an altruistic CSR. It is seen as charitable or patriotic contributions

that will remain unaccountable in terms of loss and profits. LensCrafters donates

eye exams and glasses to needy people and of Ben & Jerry’s uses five

percent of their profits to sustain causes in which its founders believe e.g.

antinuclear campaigns, gay rights groups (Lantos 2001). In some sense, these

activities are intended as contributions into the great endeavour of enhancing

the general quality of life and making the world “a better place”.

However, sceptics claim that a corporation is primarily created for economic

ends and it can never act as a welfare agency.

However, socially responsible behaviour can be embedded within the frame of

calculated actions in order to achieve strategic goal and, in the same token,

display fair and sustainable dimensions. This strategic CSR behaviour is intimately

related to the stockholder theory and to pure economics. The costs of these

strategies are looked at with a strict accountability in terms of hard return

in mind.

Section 3: The broad context of CSR within business ethics, Fairness

and Sustainability

Looking at the available literature about CSR and ethics in business, it is

easy to be convinced that the subject do have gained scholars favour and is

being now researched and discussed extensively. Many and different arguments

are put forward all of which contribute to convey the importance of CSR and

business ethics. Some of the most obvious arguments are that representing the

stakeholder and shareholder perspectives. When supported by proper motivations

and explanations, different points of view can coexist. Dissimilarities can

also be found in the definition of CSR, which has evolved and expanded during

the time. For this study the most complete and meaningful definition appears

to be Carroll’s, since it is based on both economic and non-economic criteria

embracing a full range of responsibilities of the business to the society. For

this author “CSR involves the conduct of a business so that it is economically

profitable, law abiding, ethical and socially supportive” (Carroll 1999,

p. 279). From this definition four main types of CSR can be singled out: economic,

legal, ethical and philanthropic. It means that a company is simultaneously

required to produce goods and services offered in the market, to operate within

the legal framework, to respect the ethical principles of the society and to

define and follow its own values. As can be easily understood the respect of

the legal requirements is not sufficient; conversely, “CSR begins [only]

where the law ends” (Davis 1973 in Carroll 1999, p. 274) and it means

that it is broader than the minimum standards.

CSR, from the view of stakeholder theory (Dawkins and Lewis, 2003) shows the

increasing importance of corporate responsibility in relation to stakeholders

from a wide spectrum; from consumers and employees to legislators and investors.

Other writers as Maignan and Ferrell, 2003, argue that even though businesses

adopt social responsibility based on the assumption that consumers support CSR,

there is still little knowledge of the meaning and importance of CSR for consumers

in different countries. Use of stakeholder analysis through HR practices (Simmons,

2003) examines issues of performance, accountability and equity in organizations.

In order to make a good use of a stakeholder analysis (Vos, 2003) it is vital

for managers to identify these stakeholders. Attempts to legitimize actions

and decisions with CSR connotations, (Woodward, Edwards and Birkin, 2001) are

also discussed. It is suggested that the public economy of accounting and agency

theory, in combination with stakeholder analysis is used to analyze the attitudes

towards the executives’ perceived social responsibility. Some scholars

focus on CSR’s role in development (Bryane, 2003) and give an overview

of different “schools of practices”. While others (Burke and Logsdon,

1996) examines social responsibility programmes which create strategic benefits

for the firms by identifying value created such as centrality, specificity,

pro-activity, voluntarism and visibility. Within a competitive business environment

(Husted, 2003) managers should measure return on corporate social activity as

well as return on investment. Corporate strategies can make the difference between

environmental damage disaster and pollution prevention, and responsible business

practices (Warhurst and Michelle, 2000). In the 21st century (Zwetsloot, 2003)

there is a shift from management system to corporate social responsibility in

enhancing a greater potential for innovating business practices with a positive

impact on people, planet and profit. In other words, it is a matter of good

business conduct (Beu, Buckley and Harvey, 2003) through ethical decision-making.

Thus, as recent events show, self-interest have set aside business ethics (Carson,

2003). Others writers show (Cullen, Parboteeah and Victor, 2003) that the effect

of the ethical climate depends on the organizational commitment. This can be

achieved (Dando and Swift, 2003) through transparency and assurance to close

the credibility gap. Another way to assure good business conduct (Driscoll and

Hoffman,1999) is gaining an ethical edge by delivering values-driven management.

.

Bud Reid, director of the Corporate Help Line of Lockheed Martin, in an interview

says: “we do have the external-relations office, which is responsible

for problems like supporting the community in fields like the education system.

However, we do not refer to this kind of issues as social responsibilities but

we use the term ethics”. In this case activities that are clearly part

of socially responsible programmes are still simply considered in the broad

term of ethics. CSR is the whole of the private and voluntary actions undertaken

by a company in order to support and solve problems that affect the society.

3-1/ Business Ethics, or lack thereof, have lately been discussed

as ethical distance in terms of moral responsibility (Mellema, 2003). The concept

of ethical distance helps to shed some light on situations in which several

people are involved in bringing about a state of affairs where, in order to

diminish the ethical distance, organizations need to introduce modes of “managing

morality” (Rossouw and van Vuuren, 2003). This means that organizations

will improve their sophistication in managing ethical performance. The level

of sophistication in managing ethical performance means the application of moral

principles in making choices between right and wrong courses of action (Rushton,

2002). If ethics comes from the top management who set the codes of conduct

regarding the proper business behaviour, they are also bound to achieve a good

degree of sophistication in managing the subsequent ethical performances (Schroeder,

2002), the importance of which is underlined by Schwartz, 2002. Sustainability

of economic practices is certainly achieved by play by the rules (Skrabec, 2003)

In the best of words, profit can be generated, technology breakthrough encouraged

and corporate suffocation prevented. In this sense, Webley, 2001 even suggests

to conduct a SWOT analysis regarding business ethics in order to improve sophisti

cation in ethical performance measurements. Although, it may appear a far-reaching

endeavour, this model might help to uncover potential discrepancies (VanSandt

and Neck, 2003) or gaps between organizational and individual ethical standards.

3-2/ Corporate Governance varies from country to country.

In Italy, for instance the model of corporate governance (Bianco and Casavola,

1999) is characterized by a high degree of ownership concentration both for

unlisted and listed companies. In Germany (Gugler and Yurtoglu, 2003) the dividend

pay-out policy signal the severity of conflict between the large controlling

owner and small outside shareholder. Other writers such as Lehmann and Weigard,

(2000) argue that ownership concentration is actually significantly affecting

profitability in a negative way. In a survey of corporate performance and board

structure in Belgian companies Dehaene, De Vuyst and Ooghe, (2001) found evidence

that board size and percentage of outside directors are positively related to

company size in relation to return on equity and return on assets. On the other

hand, a very British solution (Goldenberg, 2003) in reforming corporate governance

is to use combined code on corporate governance. All in all, the view on corporate

governance varies depending on the chosen perspective (Husted, 2003) but, in

all cases, it may be referred to as a choice for a particular form of corporate

social responsibility (Lai and Sudarsanam, 1997).

3-3/ Fair Management is among many things build on the discourse

of organizational justice and equity (Cropanzano, Byrne, Bobocel and Rupp, 2001).

These authors argue that it requires a formulation of an appraisal of justice

whilst the quest of Gilliland and Schepers, (2003) goes through the analysis

of that which seems to determine the just treatment in specific decisions. It

is argued elsewhere that the perception of organizational fairness (Greenberg,

2003) might be enhanced by the introduction of a formal system. Given the fact

that such system can jeopardize the perception of fairness and reduce its impact,

formally mandating fair procedures is an effective way of creating unfairness

by.

3-4/ Sustainability, would seem to be achieved, according

to Lovins et al, (2001) by natural capitalism, whereby four principles enable

business to behave responsibly toward both nature and people while increasing

profit, inspiring their workforce and gaining competitive advantages. As it

where, this is easier said than done. Putting these principles into practice

(Sweet, Roome and Sweet, 2003), taking into account the harsh environment where

corporate are operating while sustaining the good business practices demands

a special bread of managers. These must show the ability to focus on and integrate

all the different facets of their business environment. They must also show

the ability to engage in far-reaching collaborative efforts involving a multiplicity

of partners. For example the implications in the shift of power relationships

between states, firms and households (Cramer, 2002) is emphasising the trend

toward a more viable attitude to sustainable business where firms consciously

need to focus on creating socially responsible values in the same time as financial

values. Partnerships between corporations and other spheres of interest are

wished for. Juniper and Moore, (2002) report that such partnership with local

and regional stakeholders provide a whole system of solutions and lead to unexpected

benefits, including within the frame of an international context (Epstein and

Roy, 2001).

There is no doubt about the fact that the corporate social responsibility is

gaining more ground worldwide. Corporate and their leaders are moved by a strong

desire to do the right thing but they are also seeking for ways of understanding,

defining and disseminating solutions what might constitute sustainable business

practices. Sustainability is not merely a parade word; it stands for a set of

practice that constitutes responsible corporate behaviour. It is a guideline

by which one can define the intersection between the general public interest

and the interest of the firms. It is true, though, that corporate cannot act

in place of governments. Their primary goal is to make profit and ensure a good

value for their shareholders. However, there is no contradiction in the fact

that the ability of corporations to organise actions implement them efficiently

can and should be used to make the world a better place and to ensure the sustainability

of business practices. One of the CEOs from the global survey by PricewaterhouseCooper

(ibid) says:

People in the world are better educated now. Corporations should be more socially

responsible toward their employees and the public. Many companies in the US

and EU have already adopted high levels of social standards. Companies in developing

countries should follow this lead and voluntarily provide better care toward

society and their employees. Responsible companies should not only ensure that

their social standards be high; they should also enforce such high social standards

onto their suppliers” (ibid, page 25)

The Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies in partnership with

the United Nations Environment Programme has provided a mean for moving forward

toward sustainability. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) was initiated in

1977 with the aim of helping corporations with viable guidelines for their voluntary

use in order to report the economic, environmental, and social aspects of their

business activities. It is encouraging to observe that companies are paying

attention to this issue. As per January 2003, more that 180 companies have published

sustainability reports using the GRI guideline.

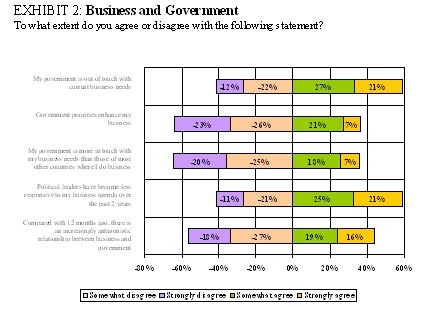

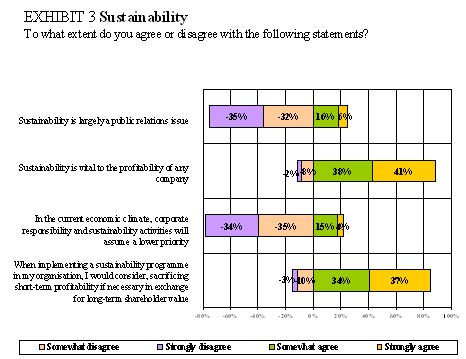

Exhibit 3 (page 26 in the PricewaterhouseCoopers’ CEO report, 2003) highlights

interesting aspects about corporations perception of sustainability. More that

67 percent of the asked CEOs think that sustainability is not merely a public

relation issue nor a parade word. On the contrary, 79 percent of them agree

that sustainability is vital for the profitability of firms. Moreover, 71 percent

state that they are willing to sacrifice the short-term profitability in exchange

for long-term shareholders value through sustainable business practices

Concluding remarks:

It is argued by many authors that a code, constituting a "a set of rules

about how people should behave or about how something should be done" (Collins

Cobuild 1997, p. 302) can be used to formally include CSR in the organisational

environment with the purpose of creating an ethical environment and positively

influencing attitudes toward issues of ethics and CSR. Other, mean that this

code is a set of "moral standards used to guide employees or corporate

behaviour" (Schwartz 2001, p. 256); (O'Donovan, 2002; Nijhof, 2002)). In

the lights of the latest corporate scandals worldwide, it appears that the majority

of these corporate, if not all, did have a code of conduct, which did not prevent

managers and employees from pursuing their personal interest and, in many cases,

leading their company into catastrophe. The code is usually the result of the

interaction among different actors such as managers, employees and other stakeholders.

When it exists as document, it is usually introduced to gain recognition and

legitimacy from the external environment. Generally, the existence of such a

document has positive effect on the stakeholders, who sees it as a sign of commitment

on the relevant nexus between business and society. The question is whether

people’s sense of integrity and perception of ethical behaviour can be

changed by codes. Codes and laws may have a controlling power to refrain the

most deviant behaviour, but, on the main, they would seem to be without effects

on the choices people make, especially those subjected to one’s own interpretations.

We have earlier in this text evocated numerous cases where crossed many borderlines

in the belief that they where doing no harms. Whether it is their interpretation

or the public expectation that are exaggerated is still open to debates. The

fact remains that we are being made aware that unethical behaviour is more in

the eye of the beholder than in the insight of the perpetrator. The public has

been shocked by news of misdeeds times after times wondering each time how could

such thing happens. However, we slowly but surely realise that it is perhaps

not a recrudescence of bad behaviour that we are witnessing, but rather our

increased awareness and intensified scrutiny of businesses and their captains.

The notion of fairness needs also to be addressed from a wider perspective,

that of the dominant school of modern moral and legal philosophy. A deconstruction

of this discourse may reveal that CSR as well as personal decisions are not

always based on the moral philosophy covering fairness, right and justice. The

argument of human welfare is perhaps better criteria for reinterpreting fairness

against the background of social and psychological theory and practices. However,

fairness, as a locus for the democratic tradition, offers an alternative to

utilitarianism, which had dominated the Anglo-Saxon tradition of political thought

since the nineteenth century. The ideal of the social contract (Rousseau; Kant;

Emerson) is a more satisfactory account of the basic regulatory processes directing

and governing people’s behaviour and actions in the complicated web of

communities.

REFERENCES

Aaronson, Susan Ariel, (2003), Corporate Responsibility in the Global Village:

The British Role Model

and the American Laggard, Business and Society Review, 108:3: 309-338.

Arrow K.(1963), "Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical care",

American Economic review, 53, P. 941-973.

Becht, Marco, (1999), European corporate governance: Trading off liquidity

against control, European Economic Review, 43, 1071-1083.

Beu, Danielle S., Buckley, Ronald M. and Harvey, Michael G., (2003), Ethical

decision-making: a

multidimensional constructions, Business Ethics: A European Review, Vol. 12,

No. 1, 88-107.

Bianco, Magda and Casavola, Paola, (1999), Italian corporate governance: Effects

on financial structure and firm performance, European Economic Review, 43, 1057-1069.

Bryane, Michael, (2003), Corporate Social Responsibility in International Development:

an Overview and

Critique, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 10:115-128.

Burke, Lee and Logsdon, Jeanne M., (1996), How Corporate Social Responsibility

Pays Off, Long Range

Planning, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 495-502.

Carson, Thomas L., (2003), Self-Interest and Business Ethics: Some Lessons

of the Recent Corporate Scandals, Journal of Business Ethics, 43:389-394.

Carroll, A.B. (1999) ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ Business

and Society n. 38 pp. 268-296

Collins Cobuild (1997) English Dictionary, Harper Collins Publishers London

Cullen, John B., Parboteeah, Praveen K., Victor, Bart, (2003), The Effects of

Ethical Climates on Organizational Commitment: A Two-Study Analysis, Journal

of Business Ethics, 46:127-141.

Cramer, Jaqueline, ( 2002), From Financial to Sustainable Profit, Corporate

Social Responsibility and

Environmental Management, 9, 99-106,

Cropanzano, Russell, Byrne Zinta S., Bobocel, Ramona D. and Rupp, Deborah E.,

(2001), Moral Virtues,

Fairness Heuristics, Social Entities, and Other Denizens of Organizational Justice,

Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 164-209.

Dando, Nicole and Swift, Tracey, (2003), Transparency and Assurance: Minding

the Credibility Gap, Journal of Business Ethics, 44:195-200.

Dawkins, Jenny and Lewis, Stewart, (2003), CSR in Stakeholder Expectations:

And Their Implication for

Company Strategy, Journal of Business Ethics, 44:185-193.

Donaldson, T. and Dunfee (2002) T.W. 'Ties that bind in business ethics: Social

contracts and why they matter'. Journal of Banking & Finance 26 pp. 1853-1865

Dehaene, Alexander, Vuyst De, Veerle and Ooghe, Hubert, (2001), Corporate Performance

and Board Structure in Belgian Companies, Long Range Planning, 34, 383-398.

Driscoll, Dawn-Marie and Hoffman, Michael W., (1999), Gaining the Ethical Edge:

Procedures for Delivering Values-driven Management, Long Range Planning, Vol.

32, No. 2, 179-189.

Fama E & Jensen M.C.(1983), "Separation of Ownership and Control",

Newspaper of Law and Economics.

Epstein, Marc J. and Roy, Marie-Josée, (2001), Sustainability in Action:

Identifying and Measuring the Key Performance Drivers, Long Range Planning,

34, 585-604.

Friedman, M. (1962) Capitalismo e Libertà (trad. Pavetto, R.) Edizioni

Studio Tesi (1987), Pordenone, Italy.

Gilliland, Stephen W. and Schepers, Donald H., (2003), Why we do the things

we do: a discussion and analysis of determinants of just treatment in layoff

implementation decisions, Human Resource Management Review,13, 59-83.

Glais M.(1992), Economie industrielle, les stratégies concurrentielles

des firmes, Paric, Litec.

Goldenberg, Philip, (2003), Reforming Corporate Governance – A Very British

Solution, Business Law Review, April, 82-86.

Greenberg, Jerald, (2002), Creating fairness by mandating fair procedures:

the hidden hazards of a pay-of performance plan, Human Resource Management Review,

13, 41-57.

Gugler, Klaus and Yurtoglu Burcin, B., (2003), Corporate governance and dividend

pay-out policy in Germany, European Economic Review, 47, 731-758.

Greider, W. ‘Crime in the suites’ in Richardson, J.E. Business

Ethics 02/03 Annual Editions. McGraw-Hill/Dushkin Fourteenth edition.

Hardjono, T.W. and van Marrewijk, M. (2001) “The social dimensions of

business excellence” Corporate Environment Strategy Vol. 8 No. 3 pp. 223-234

Hax, A. “Defining the Concept of Strategy” in De Wit, B. and Meyer,

R. (1998) Strategy: Process, Content, Context. Thomson Learning London pp. 28-32

Husted, Bryan W., (2003), Governance Choices for Corporate Social Responsibility:

to Contribute,

Collaborate or Internalize? Long Range Planning, 36, 481-498.

Jensen M.C. & Meckling W.H.(1976), "Agency Costs and the Theory of

the Firm", Newspaper of Financial Economics.

Juniper, Christopher and Moore, Maggie, (2002), Synergies and Best Practices

of Corporate Partnerships for Sustainability, Corporate Environmental Strategy,

Vol. 9, No. 3, 267-276.

‘Johnson & Johnson and Tylenol’ Available in: http:// www.mallenbaker.net/csr/CSRfiles/crisis02.html

Accessed on the 10th February 2003

Key, S. (1999) “Toward a new theory of the firm: a critique of stakeholder

theory” Management Decision 37/4 pp. 317-328

Lantos, G. (2001) 'The boundaries of Strategic CSR'. Journal of Consumer Marketing

18 (7) pp: 595-630

Lai, Jim and Sudarsanam, Sudi, (1997), Corporate Reconstructuring in Response

to Performance Decline:

Impact of Ownership, Governance and Lenders, European Finance Review, 1: 197-233.

Lehmann, Erik and Weigand, Jurgen, (2000), Does the Governed Corporation Perform

Better? Governance

Structure and Corporate Performance in Germany, European Finance Review, 4:

157-195.

Lovins, Hunter L. and Lovins, Amory B., ( 2001), Natural Capitalism: Path to

Sustainability? Corporate

Environmental Strategy, Vol. 8, No. 2, 99-108.

Maignan, Isabelle and Ferrell, O.C., ( 2003), Nature of corporate responsibilities-

Perspectives from

American, French, and German consumers, Journal of Business Research, 56, 55-67.

Mellema, Gregory, (2003), Responsibility, Taint, and Ethical Distance in Business

Ethics, Journal of Business Ethics, 47: 125-132.

Médan P. & Warin T.(2000), Economie Industrielle, une perspective

européenne, Paris, Dunod.

Moir, L. (2001) 'What do we mean by corporate social responsibility?'. Corporate

Governance 1,2 pp. 16-22

Poma, F. (1996) Economia Politica 1st edition, Principato, Milano

Rossouw, Gedeon J. and Vuuren van, Leon J., (2003), Modes of Managing Morality:

A Descriptive Model of

Strategies for Managing Ethics, Journal of Business Ethics, 46: 389-402.

Rushton, Ken, (2002), Business Ethics: a sustainable approach, Business Ethics:

A European Review, Vol. 11, No. 2,137-142.

Schroeder, Doris, (2002), Ethics from the top: top management and ethical business,

Business Ethics: A

European Review, Vol.11, No. 3, 260-267.

Schwartz, Mark S., (2002), A Code of Ethics for Corporate Code of Ethics, Journal

of Business Ethics, 41:27-43.

Skrabec, Quentin, (2003), Playing by the rules: Why ethics are profitable,

Business Horizons, September-October, 15-18.

Schwartz, M. (2001) 'The nature of the Relationship between Corporate Codes

of Ethics and Behaviour'. Journal of Ethics 32 pp. 247-262

Simmons, John, (2003), Balancing Performance, Accountability and Equity in

Stakeholder

Relationships: Towards more Socially Responsible HR Practice, Corporate Social

Responsibility

and Environmental Management, 10, 129-140.

Sweet, Susanne, Roome, Nigel and Sweet, Patrick, (2003), Corporate Environmental

Management and

Sustainable Enterprise: The Influence of Information Processing and Decision

Styles, Business Strategy and the Environment, 12, 265-277.

VanSandt, Craig V. and Neck, Christopher P., (2003), Bridging Ethics and Self

Leadership: Overcoming Ethical Discrepancies Between Employee and Organizational

Standards, Journal of Business Ethics, 43:363-387.

Vos, Janita, F.J., (2003), Corporate Social Responsibility and the Identification

of Stakeholders,

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 10, 141-152.

Warhurst, Alyson and Mitchell, Paul, (2000), Corporate social responsibility

and the case of

Summitville mine, Resources Policy, 26, 91-102.

Webley, Simon, (2001), Business ethics: a SWOT exercise, Business Ethics: A

European Review, Vol. 10, No. 3, 267-271.

Woodward, David, Edwards, Pam and Birkin, Frank, (2001), Some Evidence on Executives’

Views of

Corporate Social Responsibility, British Accounting Review, 33, 357-397.

Zadek, S. (2001) The civil corporation: the new economy of corporate citizenship.

Earthscan, London

Zwetsloot, Gerard I.J.M., (2003), From Management Systems to Social Responsibility,

Journal of Business

Ethics, 44: 201-207.

The Scandia report by Otto Rydbeck and Göran Tidström, submitted

the 25 November 2003.